Rice cultivation and elephants

Emblematic of the Sri Lankan landscape, rice paddies have shaped the island for thousands of years. A staple food for the population, rice is mainly cultivated by hand in the midst of a landscape that has remained wild.

Rice is much more than just a food in Sri Lanka: it is at the heart of daily life, agriculture and the landscape

It is impossible to imagine a Sri Lankan meal without rice. This cereal accounts for up to 50% of the calorie intake and is central to the three daily meals.

Throughout the seasons, the rice fields offer spectacular views, changing from bright green to golden hues during harvest time.

But behind this beauty lie many challenges: climate change, the precarious situation of farmers and conflicts with elephants.

A trip to Sri Lanka is also an opportunity to discover this fragile and essential form of agriculture, which is a pillar of the country's culture and food security.

Largely manual agriculture

Even before planting, work begins with water buffaloes, which are driven into the rice fields to prepare the soil.

Despite modernisation, agriculture here remains largely manual.

Agricultural machinery is rare, and animal traction remains common, especially among small farmers.

Collective farming

Rice cultivation requires a large workforce, especially during harvest time.

Many Sri Lankans combine working in the rice fields with their regular jobs.

Men and women work together, barefoot in the mud, exposed to leeches, snakes and the sun.

Two major harvest seasons

The rice harvest mainly takes place during two periods:

Maha: from September to March (the most important)

Yala: from May to August

Despite its vital importance, rice cultivation is now under threat

Climate change is causing excessive rainfall and flooding, followed by prolonged droughts, sometimes resulting in total crop losses and forcing the country to import rice.

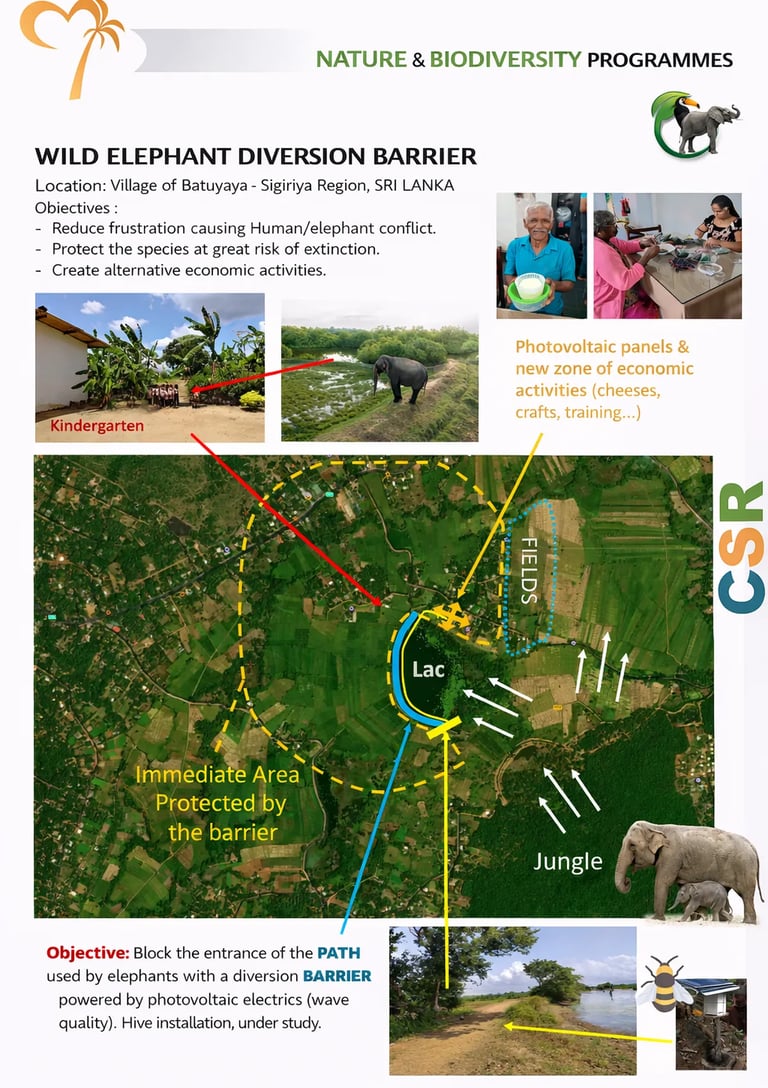

The BATUYAYA project

***

Reconciling human development and biodiversity is no longer an option, but a necessity.

Our project is part of this vision for local populations and wildlife.

****

By supporting us, you become an agent of real change and a bearer of hope.

Nearly 38% of cultivated land is devoted to rice.

Rice is generally sown from October onwards for harvesting in January–February.

If water levels in reservoirs allow, a second crop is sown in April and harvested in August.

In some regions, up to three harvests per year are possible.

A thousand-year-old culture

Rice cultivation in Sri Lanka dates back more than 6,500 years. Today's rice fields often occupy the same locations as they did nearly ten centuries ago, thanks to an exceptional irrigation system consisting of ancient reservoirs, canals and dams.

Rising sea levels are seriously affecting agricultural land.

In Sri Lanka, 223,000 hectares, including a large proportion of rice fields, have already been affected.

In some coastal areas, rice has been abandoned in favour of more resistant crops such as cinnamon, coconut and rubber trees.

The authorities are attempting to rehabilitate this land by building dams and testing rice varieties that are resistant to salinity and flooding.

Its production directly affects the food security of 22 million inhabitants.

Now that we understand the immense difficulties farmers face in growing rice, it becomes impossible to ignore another tragedy unfolding in rural Sri Lanka:

In an attempt to protect their crops, farmers often have only one option: to spend the night in simple makeshift huts made of wood and tarpaulins. They light fires, shout, bang pots and pans, and wave lamps to scare the elephants away...

...night after night...without sleep...in constant fear...

It is in this context of misery and extreme fatigue that some resort to tragic acts: elephants are injured, poisoned or killed.

The conflict between humans and elephants

When rice fields reach maturity, they become irresistible to wild elephants.

In just a few hours, an elephant can destroy months of work, trampling fields, uprooting plants and breaking irrigation systems.

Solutions exist, such as installing electric fences and warning systems, protecting elephant migration corridors, and raising awareness and actively involving local communities, in order to sustainably reduce conflicts between humans and wildlife.

FRANCE TO SRI LANKA is seeking funding to install an electric diversion fence.

It will be open, lightweight and adaptable, and will prevent elephants from:

moving around the village of BATUYAYA,

entering a nursery school, and

destroying crops or houses.

The objectives are to reduce the fatigue and exasperation of the villagers, while protecting crops.

As part of its components

NATURE &

BIODIVERSITY Programme

Harvesting is still mainly done with sickles, followed by manual threshing to separate the grains.

The vast majority of farms produce for domestic consumption. The sale of surplus crops provides only a modest income.

A unique green and golden landscape

Throughout the journey, one is struck by the nuances of colour in Sri Lanka:

During the different seasons, the rice fields change from bright green to luminous gold, offering some of the most striking landscapes on the island.

In some regions, terraced rice fields have literally sculpted the landscape, blending fields, peasant dwellings and lotus flowers.

In 2021, the sudden ban on chemical fertilisers led to a drop in yields, massive debt for farmers and soaring food prices.

Even after the measure was abandoned, fertilisers remain much more expensive, making rice cultivation unprofitable for many farmers, who have often become part-time farmers by taking on additional jobs.

These actions do not stem from hatred, but from a sense of despair.

Sri Lankans love their country, its wildlife and its elephants dearly.